Community Fridges

Community fridges are one way to feed people in need

Before COVID-19, approximately 35 million people in the United States were food insecure, including 11 million children. According to Feeding America, food insecurity was projected to increase to over 50 million people in the U.S., including 17 million children, by fall of 2020, less than a year later.

COVID-19 has increased the number of hungry people and also uncovered how widespread hunger and food insecurity were before the pandemic started. The United Nations World Food Programme estimates that global food insecurity will double in 2020 to 265 million people.

Cities scrambled to help provide more food for residents, but if food did become available, it was oftentimes over-processed and not fresh or healthy. And the need has been so great, food distribution events and pantries often ran out before everyone was served.

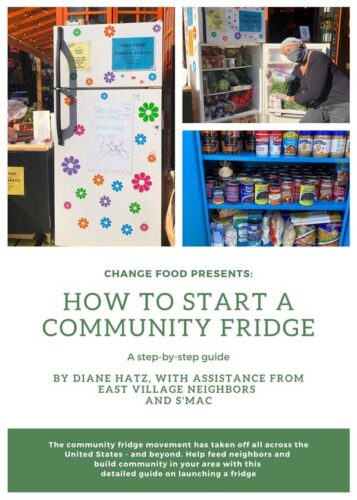

Volunteers stocking and organizing the dry food pantry at the East Village Community Fridge NYC

So neighbors stepped up. Around the world, especially in New York City, residents of neighborhood after neighborhood plugged in refrigerators stocked with fresh food outside of bodegas, restaurants and stores, and the community fridge movement took off. Many also include pantries for shelf stable food and personal care items.

The concept is simple, and the movement’s motto sums it up – Take what you need; leave what you can. Neighbors drop off unopened, uneaten food they don’t want, and other neighbors take food that they need. Volunteers take care of the fridge – cleaning, sorting, arranging shelves – as well as picking up donations from local shops, bakeries and restaurants.

Community fridges solve an immediate problem – getting food, especially fresh fruits and vegetables, directly to those who need them. Fridges bypass the roadblocks to most food pantries and government assistance – there are no forms to fill out, no identification checks. There can also be stigma attached to needing food assistance – being able to take food any time day or night helps minimize or avoid any stigma.

WHG’s Diane Hatz at the launch of the East Village Community Fridge (before food had arrived!)

Research is currently underway to count the number of community fridges around the country, but so many are starting at this time that an accurate count isn’t possible.

History of Fridges

Community fridges can be traced back to a group in Germany called Foodsharing. Around 2012-2014, the group began putting leftover food that would otherwise be thrown out (or was taken from the garbage after being thrown out!) into refrigerators around Berlin in an effort to combat food waste. Any discarded food was clean, packaged, and not in any way mixed in with other trash.

Government authorities intervened around 2016 and shut down most of the fridges, but the idea had been seeded. Community fridges most likely started in the U.S. around 2019, but they didn’t take off until the pandemic in 2020 – the number began to explode in late summer 2020 as government pandemic relief stopped and neighbors around the country stepped in to help feed each other.

The East Village Fridge. Photo by Stacie Joy

Mutual Aid

Community fridges are an example of what is called “mutual aid,” a term that simply means people voluntarily help each other and share resources. You help me; I help you. It’s that simple.

The term was used in 1902 by philosopher Peter Kropotkin who believed that cooperation was the driving force behind evolution, not competition as Charles Darwin promoted. Since then, more formalized mutual aid networks have been created in order to help streamline and share resources, but any project or group can be considered mutual aid, whether or not they belong to a larger network.

Mutual Aid became essential when the pandemic hit in early 2020. Cities and governments were unable to react quickly, so neighbors all around the world stepped in to help others who were suffering from COVID-19 and its effects.

It is as simple as checking in on the family or elderly person next door or forming groups such as East Village Neighbors, which Diane Hatz launched in her neighborhood during the pandemic. Volunteers were recruited in the area to help distribute food, shop, run errands – anything to help any neighbor in need, no questions asked. Thousands of people – or more! – around the world simultaneously, without knowing of each other, stood up and immediately took action without any rulebook or guidance – they did what they could to help others in their community.

S’MAC owner Sarita Ekya stocking the East Village fridge with the restaurant’s mac n cheese. photo by Stacie Joy

It proved Kropotkin’s point that cooperation is much more important than competition. As months went by, East Village Neighbors shifted from shopping for food to realizing neighbors needed food, so, together, local restaurant S’MAC, East Village Neighbors and Diane Hatz launched the East Village Neighbors Fridge.

Feeding Others

Community fridges are a stop gap, not a solution. They are necessary when many people are out of work and hungry, but at the same time, planning must be done for the future. No one should go hungry – and the number is growing.

Communities must stand up and solve their own problems because government hasn’t shown it can be relied on. Not only are community fridges needed, people should be trained to grow food in public spaces, as Whole Healthy Group is promoting with “Plant Eat Share.” We must pass living wage laws and not disparage new ideas like proposals for universal basic income.

Every person has the right to basic healthy food – fruits, vegetables, seed, nuts and grains – for free. No one should ever go hungry. No one.